|

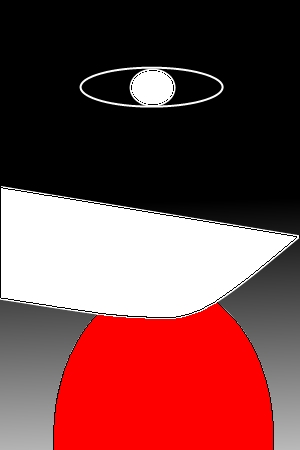

| "Handmaid Under the Eye" Created March 11, 2008 by Segeton Source: Wikimedia Commons |

According the timeline in A Handmaid's Tale, in the early 1970’s, radicals took over the United States, killing the President and all of Congress simultaneously. To erect their totalitarian regime, the country’s new founders suspended the Constitution to create their own laws. These laws are mostly anti-laws steeped in Christian sentiments, like pro-life, anti-sex (citizens are denied sex unless they are married, and even masturbating is a punishable offense), free speech censorship, and even laws prohibiting literacy (for women).

Offred is a Handmaid of the Republic of Gilead. The remnants of the United States is formed into Gilead, and woman are no longer allowed to have a job or own property in the land of Gilead. A rise in sterile men and women has prompted the leaders of Gilead to promote the use of Handmaids. Handmaids like Offred are put into households of commanding army officers to do what their sterile wives cannot: produce a child. Often, a Commander is sterile (though it is treasonous to blame men for anything in Gilead), and a Handmaid must secretly turn elsewhere to become pregnant.

When Offred’s Commander begins a courtship with her, their forbidden affair is one she takes as just another duty of her Handmaid status. Yet, the affair opens her up to another affair with the Commander’s chauffer, Nick, and she finds herself falling in love for the first time since the empire of the United States ended and the reign of Gilead began.

A Handmaid’s Tale reads like a series of diary entries, and the writing is just as intimate. Atwood is not afraid to make her characters real, even if sometimes that means their descriptions are crude beyond belief: “Below me, the Commander is fucking. What he is fucking is the lower part of my body. I do not say making love, because this is not what he’s doing. Copulating too would be inaccurate […]; Nor does rape cover it: nothing is going on here that I didn’t sign up for” (p. 121).

Female freedoms and male expectations are two large themes Atwood constantly revisits in her novel. Simple things women may take for granted like having a bank account, going where they please, reading a book, and having a job are all defining characteristics of female suffrage. Offred, and all women in Gilead, are denied these basic rights. Why? The founders of Gilead believe that by returning women to a more ‘traditional’ role (traditional role in the Christian or even Islamic sense), they can guarantee the happiness of most. Like other totalitarian governments, Gilead has achieved a few things that modern civilization has not: rape, murder, and theft have been eliminated (for the most part).

|

| Author Margaret Atwood attends a reading at Eden Mills Writers' Festival, Ontario, Canada in September 2006. By Vanwaffle Source: Wikimedia Commons |

Men of Gilead expect their women fill the role of the caretaker (cooking, cleaning, ect). In a way, women are natural caretakers as they give birth and instinctively feel the need to take care of their progeny. Does that mean that women should be responsible for taking care of all household duties, and nothing else? Well, in Gilead, that is exactly what being a woman means. Men of Gilead also expect their women to be natural sluts (but publicly, they denounce wanton sexual behavior). Gilead Commanders maintain a brothel outside of town, named the Jezebel. At Jezebel, women wear ‘retro’ costumes, like lingerie and cheerleading outfits. When Offred asks how a place like Jezebel is allowed, the Commander responds with “Everyone’s human […] you can’t cheat Nature. Nature demands variety, for men. It stands to reason, it’s part of the procreational strategy. It’s Nature’s plan. Women know that instinctively. Why did they buy so many different clothes, in the old days? To trick the men into thinking they were several different women” (p. 308).

No comments:

Post a Comment