|

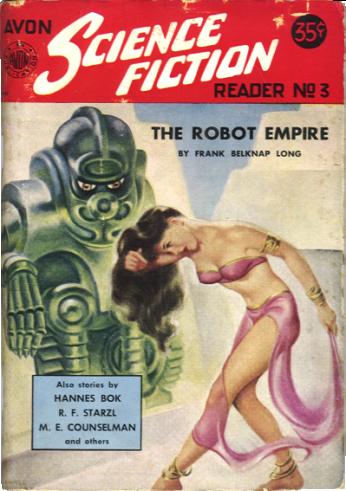

An idealized version of what the SF genre is (or was). Cover of the fantasy fiction magazine Avon Science Fiction Reader no. 3 (1952) by Frank Belknap Long Source: Wikimedia Commons |

A comprehensive (and often) exhaustive study on the validity of science fiction in the literary canon. In fact, author Carl Freedman dedicates an entire section of the book to the description, history, and importance of the literary canon and why science fiction works are to be included in the canon.

Freedman’s text redefines science fiction as ‘cognitive estrangement’, as coined by author Darko Suvian. To better understand Suvian’s meaning, a quote is rather necessary: “estrangement ‘differentiates [science fiction] from the realistic literary mainstream’, while cognition differentiates it from myth, the folk tale, and fantasy […] science fiction is determined by the dialectic between estrangement and cognition” (p. 16).

To Freedman, the genre of science fiction is constantly evolving, and it is hard to pinpoint what exactly constitutes the epitome of science fictional text. Freedman’s views of science fiction are so broad (or maybe so idealized) that he believes all general fiction to be a sub-category of science fiction, and not the other way around (p. 20). The expansive reach of the science fiction genre in Freedman’s eyes is boggling. Freedman believes that every fictional text ever written is a sort of science fictional story as well, because some apt descriptions of science fiction say it is the creation of a new world. Arguably, every fictional novel is a ‘new world’ created by the author and the characters that populate it.

In three not-so-short chapters, Freedman takes the reader on a new expedition into the academic world of science fiction. Chapter one is titled “Definitions”, and it does just that; chapter one defines critical theory and science fiction, melding the two together with Freedman’s conclusions (juxtaposed with other academic opinion of course). Chapter Two, “Articulations”, first discusses genre, literary canon, and theory. Then, science fiction is measured against three critical dynamics: style, the historical novel, and utopia. Chapter three, “Excursuses”, give detailed overviews of Solaris, The Dispossessed, The Two of Them, Stars in My Pocket, and The Man in the High Castle.

Lastly, Freedman includes a section that explores critical theory and science fiction and how it may later evolve, as Freedman concedes that “it is in the nature of critical fiction and science fiction to speculate about the future” (p. 181).

Freedman’s section on utopias and feminism make a nice addition to the academic conversation. In that same section, authors Ursula Le Guin and Joanna Russ are compared and contrasted in a very satirical manner: “The basic contrast frequently adduced is between the gentleness of Le Guin’s feminism and the angry militancy of Russ’s” (p. 129). Freedman makes fun of such comparisons, stating that they are responsible for creating further rifts for women in science fiction (or in society in general). He also muses on the fact that for early pulp science fiction of the 1900’s, it was hard for the genre to recognize able-bodied women, or admit the fallacy of phallic dominance (p. 129).

Throughout the book, Freedman’s tone is one that strives to reach the reader, but always falls a little bit short with a myriad of unknown adjectives and a mountain of footnotes on almost every page (even though in the preface Freedman expresses his own dislike of footnotes, on the grounds that it is a ‘pseudoscholarly practice of citing works in order to suggest, truthfully or not, that one has read them’ [p. xx]). Despite that, once the reader is able to follow Freedman’s ideas and take hold of them, his tone is suggestive, humorous, and down-to-earth.

Critical Theory and Science Fiction was published in 2000. That fact only becomes evident in the last section which mentions the evolutionary pattern that will take hold of science fiction, namely, cyberpunk. To an extent, Freedman is correct, so it is a forgivable error in his effort to create a timeless account of the science fiction genre. Since his studies in the book mention books in the literary canon from 1818 until the late 1980’s, the year of publication is nominal in this instance.

Generally, I prefer not to read academic texts unless they are strictly related to what I am studying. Freedman’s book was one that did not let me forget what I was studying, and it was an academic text that I highlighted like a lunatic, madly muttering to myself things like “yes….and yes…” and “of course!”. If future readers can get over the flowery detailed language in the preface, then they will count themselves lucky to have stumbled upon the fascinating overviews provided by Freedman in his three, seventy-five-page chapters.

Freedman is an associate professor of English at Louisiana State University. He is the author of several articles and four non-fiction texts. An excerpt from his book Critical Theory and Science Fiction was chosen as featured text for discussion at the Theory Roundtable of the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts in 2002.

Freedman, Carl. Critical Theory and Science Fiction. Middletown, Connecticut: Weslayen University Press, 2000. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment